The field of teaching that unfolds against this backdrop envisages creating relational, cooperative modes of learning and working in a team with teachers and students in a cross-disciplinary way, which make it possible to make creative practice reflexive and at the same time orient theory towards practice. This always means thinking together research and teaching, work and didactics. Such interplay is familiar to us from our previous university activities and also forms the core of Civic City’s work.

During our vast university work we lead courses, lectures series and seminars for students in the Bachelor’s degree programme as well as courses in the Master’s degree programme including supervision of master’s theses. We supervised doctoral students, led teaching and research units while laying a special emphasis on collaborating in teaching and researching with design studios. Within this work we discussed with the students in a reciprocal manner fundamental questions of social, economical, political and cultural circumstances and powers of the urban, contemporary sociological and theoretical approaches in urban- and housing research, and global processes.

Our specific form of didactics is a seismographic approach. We place the question at the beginning, in order to then use the develo- ped question as a structure for the further learning process. It is about developing awareness: in what context am I moving? What options can I generate and how? How can I develop awareness for questions? And: how can I constructively integrate the structures gained into the further course of the process, and generate forms, works from the resource of my own motives, which in turn sti-mulate further reflection and creativity.

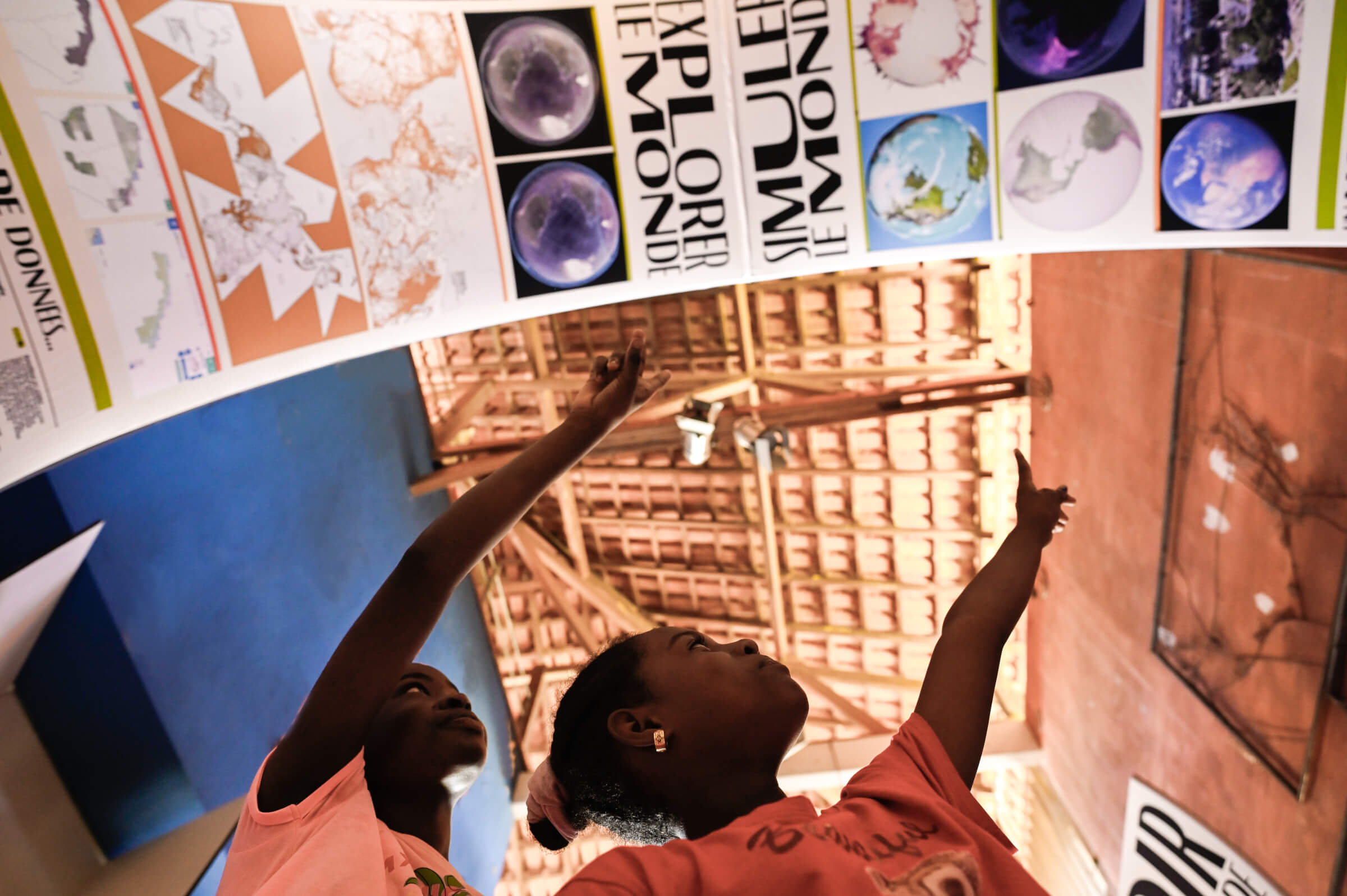

Creativity is an act of reusing and associating heterogeneous materials. In educational settings, it is therefore particularly important to make learning an act of production and the learner a producer of works and to focus on the mode of action in the learning situation: how do I make something, how do I produce something and how do I put together heterogeneous materials that interest me and are available to me?

In concrete terms, this means that learning takes place when students find themselves in situations that connect to their bodily-mental schemata of perceiving, recognising and judging, activating them and thus evoking the appropriation of space. This is particularly important in contexts in which purely formalised education is not expedient. In the situation of an astonishing lack of an available canon of forms in the interplay of urban studies and urban or architectural design, the knowledge of the terrain one moves in and its relation to an exercise and articulation of knowledge practices becomes even more relevant. It is important to follow a topology that does not simply applies forms but rather explores the knowledge space in relation to enabling strategies and creates forms.

Against this background, we in our application as duo already propose a form of cross-teaching in which educators and practitioners from different disciplines mix. It is the pursuit of a “practical project” within the seminar that enables both motivation, a sense of achievement and personal responsibility. Pedagogy would then be determined as a technical-practical rather than a moral-practical science. This aims at professionalising the schemata of lifeworld orientation, explicitly including those forms with knowledge and experience that do not follow the mode of purely linear rationality (=everyday practices). The grand formula in this case is an education that links assumption and expectation horizons to the city’s own types of processes and production constellations to form a semantic and work-oriented complex of its own, but remains connectable to internal discourses and external value types.

Coming from design, it is about an applied sociology that uses its capacity to make social architectures visible and comprehensible to support building and spatial design projects.

In recent years, contextual reflexivity, concertation, participation, resource equity and sustainability have become indispensable factors for urban planning, architecture and landscape planning. In lot of advanced architecture studios social scientists are associated and consulted in the beginning of the conception phases.

However, they often come from contexts far removed from design and remain in a supply function. Our aim is to fill this gap and to provide the future designers of our living environments with the transdisciplinary tools they need to launch innovative, but also socially and ecologically sustainable design and construction at the highest international standard.

The aim is to transmit the canon of sociological positions, but also to teach and learn together with the students what we do not yet know.

This results in new learning formats on an analog and digital level as well as in the field with direct project participation. The projects themselves become cases that are included as references in teaching. Thus, the learning material does not become an abstract entity, but a tool for the future architects, urbanists and landscape designers.

We would like to address all of these questions at the chair and make it a research pole that not only brings sociology and urban research to new horizons, but also advances design production in conjunction with the neighboring chairs and institutes in the ETH and internationally.

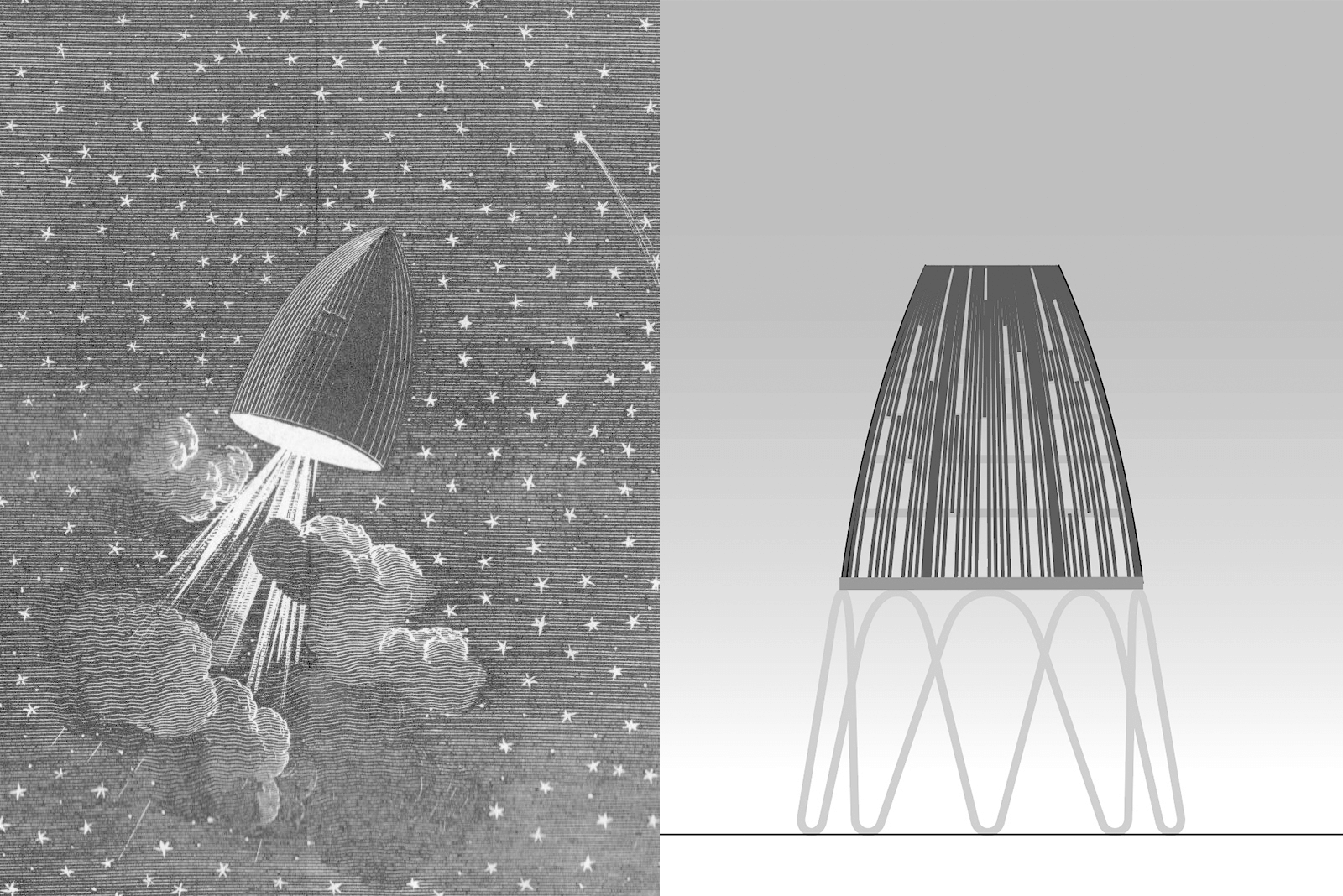

A central concern is the confrontation with the effects and impact of design, because architecture, urban design and landscape design are political acts which intervene in existing structures. In order to do justice to this task, anticipation, reflection and conception tools are needed that can systemically and openly accompany design processes and analyze their consequences. Our expertise from 30 years of building and design projects of our own studios, as well as the international network of Civic City serve as a fund of examples of highly experimental formats which did not remain merely utopian, but were translated into prototypical and realized building projects in small and large scales, thus proving their applicability. In doing so, our transdisciplinary approaches serve as a repository of methods that have had little or no application in architecture, urbanism, and landscape planning so far. In the face of global ecological, economic and social crises, where inequality has increased exponentially, we need to challenge existing concepts and bring them closer to the goal of a more just ans sustainable world.

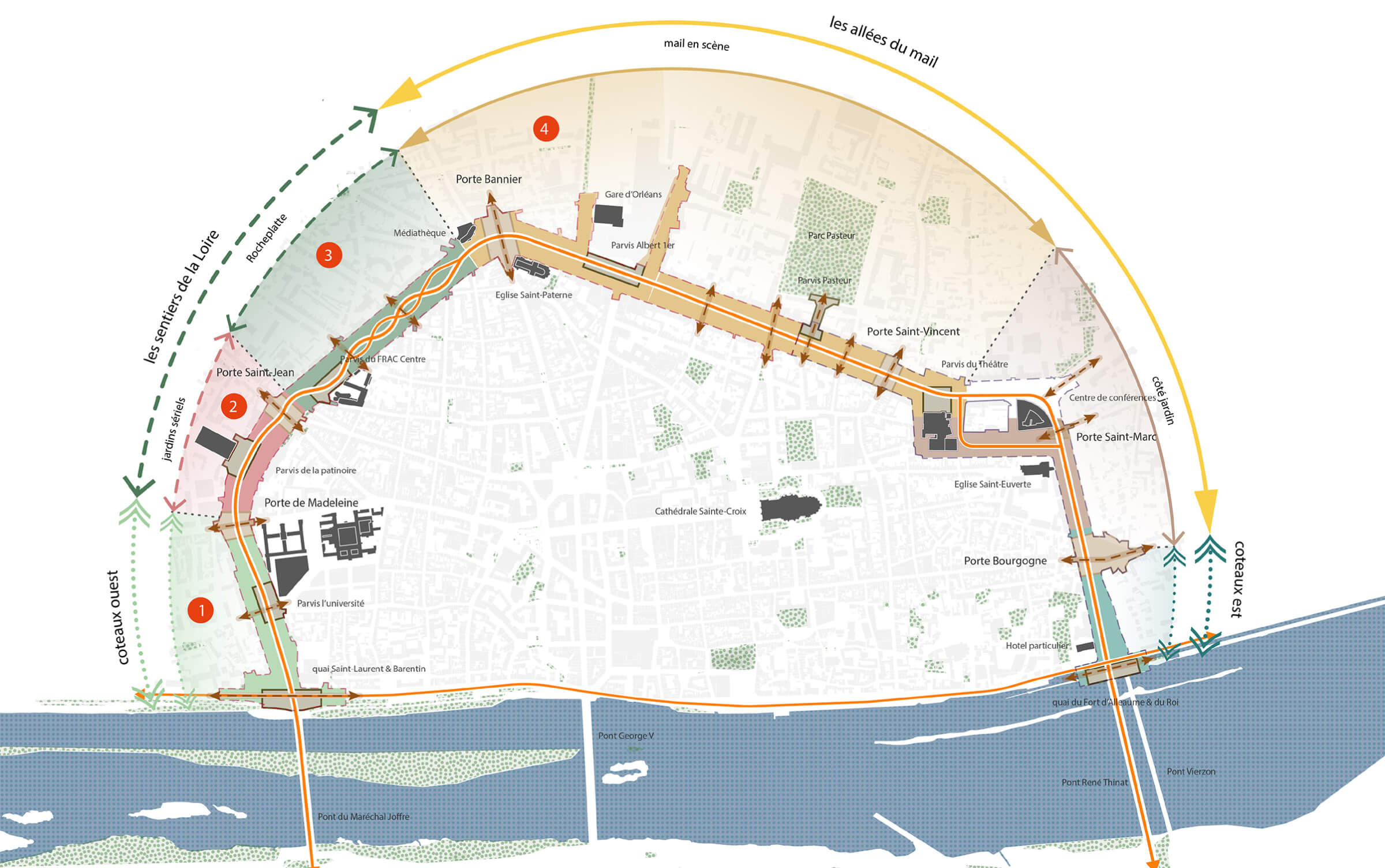

Designers of all disciplines have to assume their significant and responsible role in it. We stated an urbanization of the world population and often still follow the image of an accessible city according to the European model. Reality clearly shows that the majority of the urban population has no share or access to urban qualities and resources, but on the contrary only has to bear the disadvantages of highly dense, externalized urban spaces without sucient public infrastructure and vital resources. In the principle of an urban acupuncture, the metabolism of urban and rural systems can be reactivated and vitalized with interventions of different scales.

In this process, changing an urban imaginary or a map of relations can occasionally have more impact and get stalled urban processes flowing again than massive, protracted, and costly infrastructure projects. This interplay of di erent for- mats and forms needs to be looked at more closely and examined for its interdependent potentials.

The interventions happen processually, in which e ects and consequences are observed and designs are adapted. Therefore, with our approaches, for example, improvisation and design of relations, we are working on a concept of Energetic Urbanism, which aims at dynamic, sustainable and more equitable resource use and thinks both the hard factors, such as energy and materialized resources in connection with soft, symbolic, sensual resources.

In addition to the urbanization of the world’s population, which targets the places of bodies, a central focus is the heteronomization and digitalization of living environments, the systemic consequences of which are presented either in euphoric or apocalyptic scenarios, but are still too little integrated into a critical analysis. We see central concern in the use of the latest technological and scientific achievements in the critical mirror of a cost-benefit assessment for the overall planetary system of humans and nature.

On the one hand, we can build on our exhibition, conference, workshop, e-learning, and publication experience, and aim to develop new formats to make the generated knowledge accessible to scientific and, as far as possible, civic use.